By Mast Qalandar

Dear readers, here is another post on that great folk tale of Punjab. It already appeared in Adil Najam’s blog. Even then I reproduce this for you, as I think Mast Qalandar is a guy who has done full justice to the leading Sufi poet of Punjab when he details this ever living legend in a very lucid, very absorbing style, especially as a writer who is not a native of Punjab. I myself would never have cast an iota of a doubt over his being not a native had he not divulged it himself in this very write up.

I personally am an avid fan of his writings and this reproduction is a testimony of my feeling for his forceful pen in general and this story on Waris Shah in particular. Once you complete the read, I am sure you too will agree with me.

Of all the folk tales of Punjab, Waris Shah’s Heer is the most widely read, recited (actually, sung), commented upon and quoted love story. People have even done Ph.Ds on it. It is a very long poem, written in the Punjabi baint meter, comprising of 630 odd stanzas of 6 to 12 or more lines each. Waris Shah wrote it sometime in the 1760s.

Rural folks in Punjab routinely gather, as they always did, at the end of a hard day’s work, under a tree or a chappar (thatched canopy) to smoke hukka and discuss and share the daily news, views and common problems. It is not uncommon at such gatherings for someone to sing a few passages from Heer. Folks listen to it, mesmerized both by the melody and its contents. Older people would often quote a line or two from Waris Shah’s Heer as a piece of wisdom in their conversations. In fact, Heer is quoted by the rural folks more often than any other traditional book of wisdom.

The story of Heer and Ranjha, like all such stories, is partly true and partly fiction. But it continues to have such a powerful hold on the imagination of rural folk that they want to believe it to be true.

Numerous people have written the story of Heer before and after Waris Shah, the earliest being Damodar and probably the latest being Ustad Daman. But it is only Waris Shah’s Heer that the world knows about – or cares to know about. By writing Heer, Waris Shah not only told a fascinating story but also raised the status of Punjabi from that of a rustic language, which was mostly a spoken language, to that of a language of literature. Many believe Waris Shah is to Punjabi what Chaucer and Shakespeare were to English or Sa’di was to Persian.

Waris Shah was born in a village in district Sheikhupura but studied at Kasur. He was a contemporary of Bulleh Shah and they are supposed to have studied at the same madrassah (not necessarily in the same class) under the tutorship of one Hafiz Ghulam Murtaza Makhdumi Kasuri.

Waris Shah by all accounts was a spiritual man, well versed in Islamic theology, but he was more of a mystic than a “maulvi”. In fact, going through his Heer one cannot help but wonder if Waris Shah were alive today would he be able to, or allowed to, write a daring epic like Heer?

He wrote the story while staying at the hujra (quarters) attached to a little mosque in village Malka Hans, which falls in district Pak-Pattan (old district Sahiwal).

It is said when Waris Shah completed Heer he showed it to his teacher. The latter was rather disappointed to see his talented student, instead of writing something on fiqh or shariah, had chosen to write a love story. He is reported to have said:

“Warsa (deflection of the name, often used in Punjabi to address juniors in age or rank), I am saddened to see that my efforts have gone waste. I taught both you and Bulleh Shah. He ended up playing the sarangi (a string instrument) and you have come up with this.”

Waris Shah then opened the book and started reciting Heer. As the teacher listened, the words slowly started sinking in. He wasso touched by the language, the poetry, the powerful imagery, the intensity of emotions, and the melody that he is famously reported to have said,

Waris Shah then opened the book and started reciting Heer. As the teacher listened, the words slowly started sinking in. He wasso touched by the language, the poetry, the powerful imagery, the intensity of emotions, and the melody that he is famously reported to have said,

“Wah! Waris Shah, you have strung together precious pearls in a twine of “munj” (a coarse string of hemp or jute).”

Some commentators interpret the “pearls” in the teacher’s comment as the deeper spiritual meanings and the “twine of munj” as the coarse theme of physical love. In other words, they say, you would, if you care to, find profound meanings beneath the superficial words of the story. However, others interpret the comment to mean that such beautiful thoughts and powerful images are expressed in a language (Punjabi) that was considered coarse or not quite as sophisticated at the time. Having myself sped through the book I tend to agree with both the views. (I must confess, however, that, Punjabi not being my native tongue, it was not easy for me to fully understand the text. I had to rely mostly on the Urdu translation provided alongside the Punjabi text.)

Shorn of all the embellishments and detail – the devil, in this case, though, literally lies in the embellishments and the detail – here is the story for those who may not have read it or heard it before.

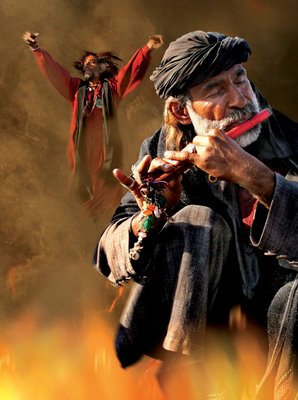

The events of the story are supposed to have occurred sometime in the middle of the 15th century. Ranjha (his given name was Deedho. Ranjha was his clan) was born in Takht Hazara, a town in district Sargodha, to a local landlord. He was the youngest of eight sons, and his father’s favorite. While others went about their daily chores Ranjha whiled away his time playing the flute that he loved so much. He grew long hair – longer than men usually wore those days – and was a very handsome young lad.

When their father died, a dispute arose between Ranjha and his brothers over the distribution of land. The brothers had apportioned the best land to themselves and gave Ranjha only the barren land. Ranjha, after a heated argument with his brothers, left home in protest. He headed aimlessly southward along the River Chenab until he reached somewhere near the present day Jhang where the Sayyal tribe ruled.

An incident that stands out during this part of the story, which has been described in great detail by Waris Shah, is when Ranjha stays in a village mosque for the night. In the quiet of the night, tired and distressed that he was, Ranjha starts playing the flute. The village folks, when they hear the poignant notes are attracted to the mosque. The maulvi of the village also turns up, not to listen to the flute, though, but to scold Ranjha for desecrating the mosque. The maulvi denounces Ranjha for playing the flute in the mosque and also for his long-haired looks, and tells him to leave the mosque. Ranjha is not intimidated and replies:

“You and your kind, with your beards, try to pretend to be saints, but your actions are that of the devil. You do evil deeds inside the mosques and then mount the mimbar (rostrum) and quote scriptures to others …”

(In fact, Ranjha is more explicit than what I have been able to paraphrase.)

The back and forth denunciations between the maulvi and Ranjha continue for some time. Interestingly, the village folks don’t seem to share the maulvi’s enthusiasm in denouncing Ranjha. They simply watch the scene as silent spectators. (Fortunately for Ranjha the blasphemy law was not in vogue then.) Anyway, Ranjha spends the night in the mosque and leaves early next morning. After a few days he ends up in Jhang.

The chief of Jhang at the time was one Chuchak Sayyal who had an extraordinarily beautiful and a headstrong daughter named Heer. Waris Shah describes her beauty and physical attributes, literally from head to toe, with the usual poetical exaggeration. Some of the analogies and metaphors he uses may sound a bit unfamiliar and even strange to the present day readers. For example, Waris Shah says:

“Can any poet sufficiently praise Heer’s beauty? Her face shines like the full moon. Her eyes are like the narcissus flower. Her eyebrows are like a Lahori bow (I didn’t know that Lahore was ever known for making bows). The kohl (kajal) in the corner of her eyes suggests as if the armies of Punjab have invaded Hind (India). Her lips are like red rubies. Her chin is like a selected apple from the King’s orchard. Her nose is like the pointed end of the sword of Hussain (!). Her teeth are like the white petals of champa flower and sparkle like pearls. She is tall and straight like a cypress in the garden of Paradise. Her neck is like that of a koonj (a species of cranes). Her hands are smooth and soft like a chinar leaf (similar to maple leaf) and her fingers like lobiay ki phallian (pods of beans, which are longer than most other pods). In short, her features are like a beautifully calligraphed book.”

Heer, when she meets Ranjha, is instantly taken by his wild and romantic looks and the soulful tunes of his flute. She persuades her parents to hire Ranjha as a cowherd for their cattle. Ranjha is hired, and thus kindles a blazing romance between Heer and Ranjha that lasts for several years, and has since been recounted and sung for almost 250 years. The two lovers often meet in the forestland along the river (known as bela in Punjabi) where Ranjha takes the cattle to graze. While the cattles graze Ranjha plays his flute. And Heer listens by his side. The days and months pass in total bliss – and very fast.

Heer’s uncle, Kaido, becomes suspicious and starts spying on her. He gathers sufficient evidence to report the matter to her parents. The parents admonish Heer on her conduct and warn her of terrible consequences. When Heer is not deterred they call in the village Qazi (a Muslim judge who decides disputes between people in the light of Sharia and also solemnizes marriages) to counsel her.

The Qazi tells her mildly that good girls, when they come out of their home, keep their gaze lowered; that they always keep their families’ honor uppermost; that they better spend their time in tiranjans (places where village women gather to spin yarn on spinning wheels and chat). He also reminds her that, being from a higher caste and a renowned family, it is unbecoming of her to mingle with family servants like Ranjha. Heer is not convinced and tells the Qazi:

“You cannot wean away an addict from the drug. It is not possible for me to walk away from Ranjha. If it is our destiny to be together then who, other than God, can change it?” And then she adds rather philosophically: “True love is like a mark that a hot iron burns on to the skin or like a spot on a mango fruit. They never go away.”

Seeing that Heer is admant the Qazi threatens her with a fatwa of death. But Heer remains unshakeable. Exasperated, Heer’s parents decide to marry her to a man named Saida Khairra from village Rangpur (Muzaffargarrh district). Nikah ceremony is arranged and the Qazi is invited to perform the ceremony. As is customary, the Qazi first asks the bridegroom if he would accept Heer as his wife, which, of course, the bridegroom readily does. Then the Qazi asks Heer and her answer is a loud No. When the Qazi insists for an affirmative answer, Heer says forcefully:

“My nikah was already made with Ranjha in heavens by no less a person than the Prophet himself, and was blessed by God and witnessed by the four angels, Jibraeel, Mikael, Izarael and Israfeel . How can you dissolve my first nikah and marry me a second time to a stranger? How is that permissible? “.

The Qazi is dumbfounded and angry, and tells Heer to shut up or “he will have her lashed with the whip of Sharia”, and goes ahead and solemnizes the marriage, anyway. After the ceremony Heer, in tears, is bundled off to Rangpur amidst great pomp and celebrations.

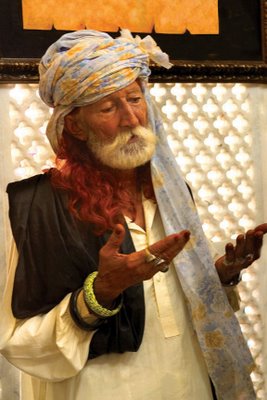

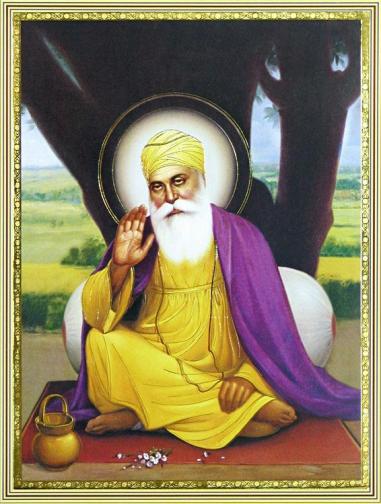

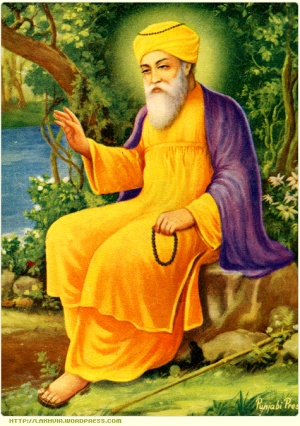

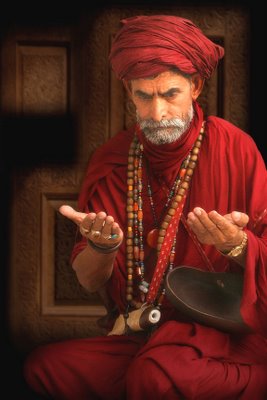

Ranjha, alone and heartbroken, takes to the jungle and joins a group of jogis (yogis). Dressed like a jogi, with ash rubbed on his body, wearing large earrings and carrying a begging bowl, he goes from house to house and village to village seeking alms – and also trying to find the whereabouts of Heer. Meanwhile, Heer languishes in Rangpur, pinning for Ranjha.

Waris Shah uses a lot of ink and a lot of pages in describing the heartache and anguish that both Heer and Ranjha suffer during this period. Amrita Pritam (died 2005), a great Punjabi poet and novelist refers to this pain and anguish, in a different context, though, in her memorable poem, when she addresses Waris Shah in these words:

Ik roi si dhee Punjab di,

Toon likh likh maare vaen

Aj lakkhan dheeyan rondiyan,

Tainu Waris Shah noon kehn

When one daughter of the Punjab wept

You penned a thousand dirges of lament

Today a hundred thousand cry out to you

To make another statement

Eventually, Ranjha finds Heer’s village and Heer also comes to know through her friends that the young handsome jogi in town was no one else but Ranjha. The two meet and, with the help of Heer’s friends and her sister-in-law, Sehti, manage to elope one night.

The Khairras follow them and capture them in the territory of one Raja Adli (a raja, not to be confused with Ranjha of the story, is a ruler of a territory or state). The lovers are brought before the raja. He asks the local Qazi to decide the case according to the Muslim law. The Qazi, without much ado, declares that Heer belongs to Saida Khairra, her “lawful” husband.

Heer and Ranjha are both devastated, but helpless.

When Heer is being forcibly taken back by the Khairras to Rangpur a forlorn Ranjha, still dressed as a jogi, raises his hands skywards and begs loudly:

“Oh, Lord, you are also Qahar and Jabbar. Destroy this town and these cruel people so that justice may be done.”

Coincidentally, a huge fire erupts in a part of the town. The village folks as well as the raja, being superstitious, are convinced that the fire was the result of the jogi’s prayer and might consume the whole town. The raja immediately proceeds to undo the “wrong” administered by the Qazi, stops the Khairras from taking Heer away and holds court to hear the case anew. After listening to all the sides he decides to allow Heer to go with Ranjha.

Joyful, Heer and Ranjha leave for Jhang Sayal expecting to live happily thereafter. However, the Sayyals, believing their honor was soiled by the unconventional behavior of Heer, conspire to “cleanse” their name of this ugly stain. While appearing to welcome the couple they suggest that Ranjha go home and bring a barat to take Heer as a wife in a proper conventional manner. Ranjha happily agrees and goes back to his brothers in Takht Hazara, who by now have forgotten their old quarrel and are also remorseful. He informs them of his planned marriage. Preparations begin for taking a colorful barat to Jhang and bring Heer home.

Meanwhile the Sayals quietly poison Heer. She dies. A messenger is sent to Takht Hazara to inform Ranjha of the unexpected and sudden death of Heer. On hearing the news Ranjha collapses and dies there and then. Thus ended the lives of Heer and Ranjha. But they continue to live in the hearts and hearths of the people across Punjab and elsewhere – and so does Warish Shah.